From: CreatiVeConnecTions

Over the last five years, a trend has been emerging with several notable nonprofit theatres making a shift in executive management structures. Spurred by internal reckonings of certain institutions’ biased histories and/or the recent racial and social justice movements, such as Black Lives Matter, the Me Too movement, and Stop AAPI Hate, some theatres have moved from a traditionally hierarchical model of management to shared, lateral leadership. The Oregon Shakespeare Festival, Soho Rep, Ensemble Studio Theatre, American Shakespeare Center, and the Wilma Theater, amongst others, have made the transition to jointly distributed leadership between multiple departments and/or directors.

The move toward theatrical co-management has largely been to decentralize institutional power. In the case of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, “Scarlett Kim and Mei Ann Teo will join associate artistic director Evren Odcikin to comprise a three-person, non-hierarchical team of associate artistic directors, who will be charged with, respectively, Innovation and Strategy, New Work, and Artistic Programming,” shares American Theatre Magazine. “These three associate ADs will work together to transcend traditional text-centric models and give centrality, priority, resources, and space to generative theatre artists across media and professions.” The Oregon Shakespeare Festival made this lateral move in 2021.

Other theatres have similar stories of wanting a “new, inclusive distributed leadership model that emphasizes collaboration, equity and diversity,” as Brandon Carter, the artistic director of the American Shakespeare Center, emphasized to News Leader.

While it is deeply commendable that these theatre companies are hiring several executive leaders to create more access to positions of leadership, filing a slot that has historically been held by one with multiple people may make the cost of executive compensation rise. With more executive and artistic directors at the helm of these institutions, I began to wonder:

Does having more members of an executive leadership team equate to more fundraising prowess for a theatrical nonprofit? Or, do more executives cost the company money/profitability, eating away at any donations that these additional leaders may bring in?

It is the legal and ethical responsibility for executive management in a theatrical nonprofit to participate in fundraising and development for their organization according to the duties of care, loyalty, and obedience. A 2021 study from Notable Ambition, an Australian philanthropic financial consulting agency, surveyed nearly 200 executive directors, financial officers, and board members about “providing insights into the role of senior leadership in driving fundraising and philanthropy engagement, impact and success.” The study revealed that 95% of participants believe that executive directors are essential to fundraising success. For executive directors, 52% reported facing a barrier of time when dealing with fundraising, and 23% cite a lack of staff resources to support their fundraising efforts.

It would be plausible to imagine that if there were more executives in shared management positions, the time constraints and lack of staff support concerning fundraising would be alleviated. So, I decided to dig deeper into the data.

Since this transition to co-management is a newer trend, there are only a few theatre companies that have 990 tax forms, publicly available forms from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) which denote the fiscal health of a tax-exempt nonprofit, that are reflective of additional senior managers. Unfortunately, the IRS has been delayed for several years in releasing 990s to the public because of the COVID-19 pandemic. ProPublica, an investigative journal and source of nonprofit organization financial information, states on their Nonprofit Explorer website that “the Internal Revenue Service is substantially delayed in processing and releasing nonprofit filings.” In fact, “the gap in reporting has become so profound that state charitable enforcement officers are sounding the alarm. In November [of 2022], the National Association of State Charity Officials sent a letter urging the IRS to address backlogged 990 data releases,” ProPublica shared. Nearly half a million tax records are missing.

Since filings are inconsistent, researching the 990 forms of any company that has moved to shared management post-2020 is difficult for comparative analysis. This got me researching modern theatre companies that lateralized pre-2020 and have consistent 990s over the past decade.

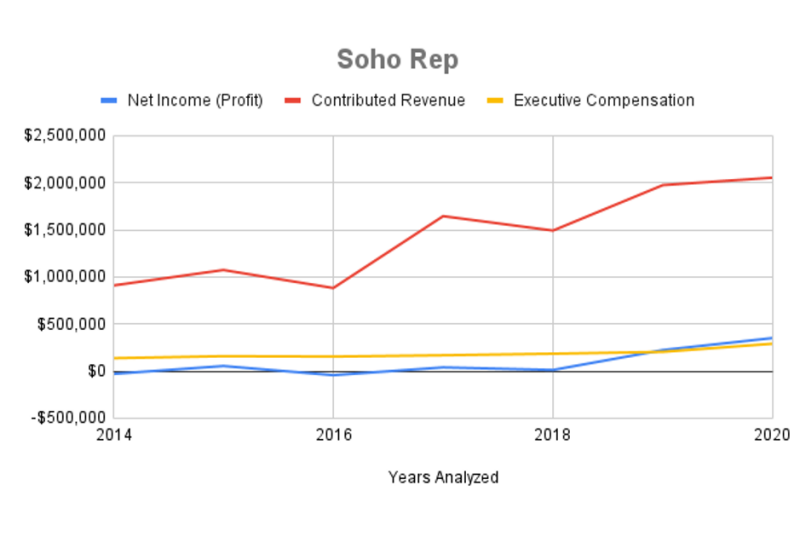

One such company is Soho Rep in New York City, which lateralized in 2018 when the artistic director position expanded to include two additional directors for a shared-power, three artistic director system. In analyzing Soho Rep’s 990 tax forms between 2014 and 2020, I was curious to see if there was a correlation between the amount of annual donation funding received (or contributed revenue) and the hiring of multiple artistic directors.

Would the amount of compensation for the additional executives cancel out in relation to the amount of new donations? Would the net income/profitability of the theatre company decrease with new expenses to the company’s budget? An interesting trendline emerged once I compiled the data.

The hiring of the two additional artistic directors only added a 3% expense increase to the overall budget of Soho Rep between 2018 and 2020. According to the graph above, we see an increase of over $500,000 in contributed income between 2018-2020. We also see the net income of the company increase, and even surpass the cost of executive compensation, revealing that the two new directors may have brought more profitability and contributed revenue to Soho Rep as a whole.

While these initial findings are positive, the hypothesis that shared management could lead to fundraising success is one that will need to be carefully evaluated over the course of the next several years. More data analysis would need to be conducted, including how much government funding was part of 2020 and 2021 contributed incomes, as many theatre companies received emergency grants during the pandemic. Since it is difficult to create a current comparative analysis of theatres during this previous period of inconsistency, a clear answer has not yet arisen from the still settling pandemic dust. In discussing the distributed leadership trend with Leah Maddrie, the Development Research and Grants Associate at Lincoln Center Theatre, she agreed that while “we will have to wait many years for a stable enough period when the financial results of lateralized management can be accurately measured, this is surely a trend to be watched.”

Regardless of the tenuous period that American theatre has been through, the chart above may be promising for companies that are interested in decentralizing their executive power in lieu of a more egalitarian leadership structure.

As the IRS is able to release more 2020-2022 financial documents, we will begin to see if the trend towards lateral management could be what nonprofit theatres need to support robust fundraising, even with the impending recession predicted for later in 2023. Not to fear, friends–perhaps we have come across a way to not only raise donations more successfully, but to create an artistic habitat of communal leadership that could usher us into a new era of theatrical collaboration, executive or not.